Special Reports

The sad end of Kwadwo Njorfuni

Report by Manasseh Azure Awuni, December 2012

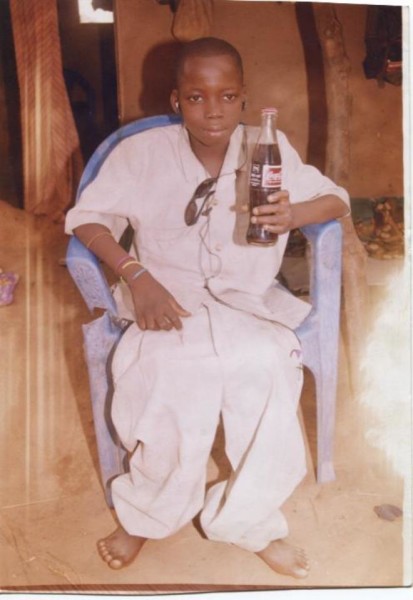

Kwadwo Njorfuni after his first surgery at Korle-Bu in 2008

The Bad News

It was bad news. It was not the kind of news 52-year old Njorfuni Wajah wished to hear after travelling more than 600 kilometres with his ailing son to the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital (KBTH). That was not what his wife, Victoria, who cannot tell her age but looks like someone in her mid-thirties, wanted to be told. And that was certainly not what 11-year-old Kwadwo Njorfuni, who is paying dearly for his father’s decision to educate him, wanted to know of his future.

But greater burden at this moment, perhaps, lay on Dr. George Wepeba, a consultant neurosurgeon at the KBTH, who had to confirm the couple’s fears after close to 30-minutes of physical examination, scrutiny of past medical records and a stack of X-ray films which Kwadwo’s father brought with him to the Hospital. Wearing an I’m-sorry-but-that-is-it look, Dr Wepeba had the onerous task of telling the couple what contradicted their expectation, what would dash their hopes.

Kwadwo would not be able to walk for the rest of his life, Dr Wepeba told the couple. He had lost the ability to pass urine so a urinary catheter would forever be connected to his penis, else he would always wet himself anytime there was the urge to empty his bladder. He had lost the ability to control his bowels and would forever wear diapers in order to soak the involuntary discharge of faecal waste.

Kwadwo had also lost his manhood, Dr. Wepeba added.

“So what can be done about it?” Mr Wajah asked after an awkward silence that came in the wake of Dr. Wepeba’s bombshell. He was hopeful that something could be done about his son’s condition once he got to Korle-Bu. That turned out differently.

The doctor said Kwadwo needed to be put on special diet, especially high protein meals. Kwadwo’s life-threatening bedsores, he said, drained him of lot of nutrients so he needed special care to survive. This imposed cost implications on the impoverished family.

“I’m very sad we could not intervene surgically again,” said Mr. Selorm Azumah, one member of the group that had sponsored Kwadwo’s transportation to Korle-Bu and paid for all the expenses. He was with the family at Korle-Bu and stood beside Kwadwo’s father in the consulting room.

Kwadwo was taken back to Banda. His bedsores, the doctor advised, could be treated at the nearest health facility instead of the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital. Disappointed but without any option, Kwadwo’s family found their way back home to hope that a “miracle” would happen in the life of their son as Mr Serlorm Azumah said.

Kwadwo Njorfuni on hospital bed

The Banda Tragedy

Kwadwo Njorfuni was among ten pupils of the English Arabic Primary School in Banda in the Krachi West District of the Volta Region who were seriously injured in 2008. A weak classroom wall collapsed on them. One pupil, Godwin Ayensu, died on the spot while seven others, including Kwadwo, survived with scary scars of the November 21 tragedy.

Kwadwo’s father was able to send him to the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, where medical authorities said he had suffered from “fracture dislocation of T11-T12 with cord transection” or spinal fracture, in lay terms. After the surgery, he was asked to come back for a medical review in six months. But he could not go because all attempts by his father, a peasant farmer, to get money failed. This visit to the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital was facilitated and financed by some individuals who felt touched by the story, which was carried by this reporter.

Dr. George Wepeba was not sure whether the medical review could have put Kwadwo back on his feet but he says lucky patients who reported early enough for the review were able to walk again after similar operations. He however said Kwadwo could have been better if his parents had carried out the recommendations by doctors at that time and provided the boy with physiotherapy.

Mr. Wajah said his son’s predicament some three and a half years ago had brought hardship to the family. His eldest son, he pointed out, was the one farming to cater for the family while he and his wife spent much of their time taking care of Kwadwo.

Mrs. Wajah said before Kwadwo’s accident, she had taken a loan of GH¢1,000 from someone in the community to engage in petty trading. She said the business had collapsed and she could not repay the loan.

“Before we came here, were spent almost six months at the Krachi [Government] Hospital,” Mr. Wajah said. He also said he was unable to repay the monies he had borrowed from people for the initial surgery Kwadwo underwent in 2008. He said he had regretted taking his son to school.

“They [educational authorities] often say we should take our children to school; what is the benefit of this kind of education that leaves the family with so much debt and suffering?” he asked.

Students of Nandikrom D.A. Primary School repairing their roof before classes

Classrooms or Death traps?

Three years after the accident, the educational infrastructure in the Banda town, where Kwadwo suffered his spinal injury, has not seen any improvement. “The classrooms are more or less death traps so we have asked the students to sit outside,” said Lapoah Alfred, the head teacher of the Banda D/A Junior High School, the best school in the district according to the 2010 Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE) rankings.

The immediate past District Director of Education for the Krachi West District, Mr. Bernard Akara, said most of the school buildings in the district were not fit to house human beings. “Sometimes you wonder whether they are hencoops or classrooms,” he said. Such deplorable infrastructure coupled with the non-availability of teachers account for the poor performance of students in the Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE) in the district.

For the likes of Kwadwo Njorfuni and the other injured children of Banda, the price they paid for education in rural Ghana is beyond failure in their exams.

“I took Kwadwo to school to learn but I have regretted taking that decision,” Kwadwo’s father said. But Kwadwo still had hopes of getting better and going back to school one day.

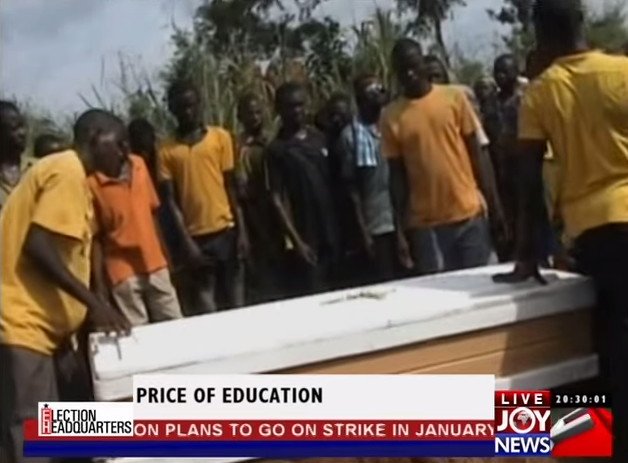

Kwadwo Njorfuni’s remains at Banda Public Cemetery

Kwadwo dies

The kind of songs students of Banda sang when they welcomed Kwadwo back from the hospital, however, meant that his dreams had come to an end. Kwadwo passed away after four years of fierce resistance and indescribable suffering.

Outside the family’s thatched house in Banda, where a short burial ceremony was held for Kwadwo, his distraught mother leaned speechlessly against the mud wall. But his father said the family was relieved that it was all over. He and his wife would now have time to work and cater for the rest of their children.

Inside the room lay the emaciated body of Kwadwo wrapped in an old and oversized grey shirt and trousers. A short debate ensued after he was lifted and put in a cheap wooden coffin. Before the coffin was nailed some of the people gathered in the room opposed the idea of burying him with the new pair of green bathroom slippers popularly called “aka me last” or “Charlie wote.” But they lost the fight and as the hammer hit the nails deep into the coffin, Kwadwo lay sideways with his feet tightly gripping the slippers.

Kwadwo was buried at the Banda public cemetery. This is where Godwin Ayensu, who died in the same accident, was buried four years ago. Kwadwo Njorfuni’s life and suffering have ended but clouds of danger still hung over students of Banda and perhaps many more across the country who study in classrooms turned death traps.

Education was the major issue for political parties in the just-ended parliamentary and presidential elections. But matching past electoral promises on education against concrete achievements of elected governments, it does not seem much will change until politicians stop focusing on the next election and spare a thought for the next generation.

-

Random Thoughts10 months ago

Random Thoughts10 months agoA Dutch Passport or a Ghanaian PhD?

-

Foreign News10 years ago

Foreign News10 years agoEvery Animal Meat Is Not Beef! See All Their Names

-

Manasseh's Folder12 months ago

Manasseh's Folder12 months agoManasseh’s Praise and Criticism of Akufo-Addo’s Action on the SML Scandal

-

Guest Writers9 years ago

Guest Writers9 years agoProf. Kwaku Asare writes: Nana Akufo-Addo has no law degree but…

-

Manasseh's Blog Posts9 months ago

Manasseh's Blog Posts9 months agoWho Started Free SHS?

-

Manasseh's Folder9 months ago

Manasseh's Folder9 months agoIs Napo Arrogant? And Does It Matter?

-

Anti-Corruption9 years ago

Anti-Corruption9 years agoMANASSEH’S FOLDER: Unmasking Afenyo Markins, NPP’s apostle of integrity

-

Manasseh's Blog Posts2 days ago

Manasseh's Blog Posts2 days agoA tribute to Naa Ashorkor