Special Reports

Special Report and Photos: A Boy’s Wish

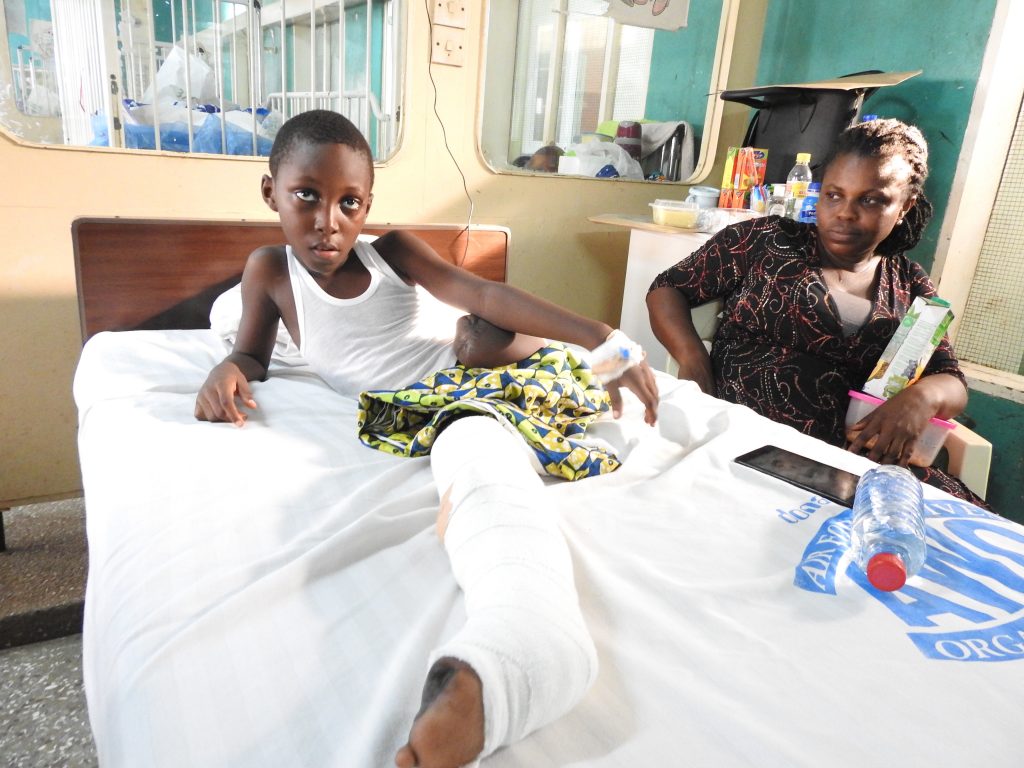

Jeremiah Arthur and his mother after his surgery at the 37 Military Hospital in January 2017

Mr. Kwabena Bukari, the assistant head teacher of Garrison Basic School in Takoradi, was seeing off a female visitor when he heard a loud bang, “Gbam!” A vehicle had jumped over an open drain and landed on the school compound.

He and his visitor were by a blue container, which served as the library of the school. When he raised his head, he saw a vehicle advancing menacingly like a ferocious lion that was about to pounce on its prey. He had no time to think, no time to ask questions. In a split second, his instinct took a decision. And his feet obeyed.

There is no consensus on the exact time of the deadly crash and crush, but the official time recorded in a police report is 15:28 GMT. Until that minute, June 2, 2016, was an uneventful Thursday in the school. School was over and a good number of the children had left. About half a dozen children were still waiting to be picked-up by their parents. This space is a concrete floor, about the size of a volleyball court.

“It is the safest spot in the school,” says Madam Elizabeth Cofie, the head teacher of the school at the time. “That’s where the students wait for their parents to pick them.”

If you stood in front of the container library and looked away from it, you would face the Gladys Asmah Street, which is the eastern boundary of the school. If you follow this street with your eyes, a few metres to your right, it hits a T-junction at the Services Schools Street. At this T-junction, the Services School’s Street descends to the left away from the school and goes to the Takoradi town. The right turn borders the school and climbs up towards Beach Road. Between this school and the two roads are open drains or gutters, which separate the streets from the concrete platform, where pupils wait to be picked up.

The white marking shows how the vehicle entered the school compound. The wall was not build at the time.

It was considered the safest spot on campus because if a vehicle veered off the road, it would definitely fall into the open drain. That posed no danger to pupils waiting to be picked in front of the library. On that day, however, it was the most dangerous spot in the school.

A Toyota Corolla with Registration Number WR 1225–6, descended from the Gladys Asmah Street, hit the T-Junction at the Schools Street, turned right and began to climb towards Beach Road. After about 10 metres of climbing, the vehicle, as if possessed by supernatural powers, made a 90-degrees turn. It jumped the open gutter, landed on the waiting area and continued towards the library.

The platform where Jerry and his colleagues waited for their parents

Jeremiah Arthur, a six-year old Primary One pupil, was among the children in the waiting area.

Jerry’s mother, thirty-eight year old Betty Mensah was in the kitchen that afternoon. Betty, a food vendor at Bompeh Senior High School, had bought ingredients and started to prepare for the following day. From the kitchen, she heard a shrill voice screaming her name.

“Jerry Maame! Jerry Maame!”

When she rushed out, she realised it was Christian, a boy in the neighbourhood who often passed by accompany young Jerry to school. Betty did not need to ask any question. Christian started speaking as soon as he spotted her: “Jerry has been knocked by a car and has had his leg chopped off,” Christian said, still panting.

“At that point I grew weak. My breath was failing,” Betty Mensah recounts.

“I told her to ignore the boy because children could say anything,” Olivia Addae, a 58-year old woman who lives in the same house recalls how she tried in vain to tame Betty Mensah’s emotions.

“I told her that children don’t lie. What they hear or see is what they report so Christian would not be lying about Jerry if it had not happened,” says Betty.

Betty and Olivia stopped everything they were doing and jumped into the next available taxi they could find. Once seated, they told the driver to drive to the hospital closest to Jerry’s School. When they got to the “European Hospital”, they were told a medical case that fitted their description had been brought there but had been referred to the Ghana Ports and Harbours Authority Hospital.

When they got to the “GHAPOHA Hospital”, the nurses said they had received a call that such a case was on its way to the hospital and they had prepared the theatre but the case did not come. The suggestion was that they should go to Effia Nkwanta Regional Hospital.

The open drain between the school compound the the streets

At the hospital, the first person Jerry’s mother noticed was his son’s head teacher, Elizabeth Cofie.

“From the way the head teacher was behaving, I didn’t need to ask further questions. I started crying,” Jerry’s mother says. She was prevented from going to see her son. What had happened earlier in the day had shocked everybody and not many of them could bear to see Jerry in that condition. And they thought her mother should be spared the bloody scene inside the hospital. For those who witnessed it in the school, it was gorier.

Panic-stricken Jerry and his colleague pupils had been closer to the danger than their teacher, Mr. Bukari, and his friend. They reacted the same way the teacher and his friend did. In different directions, they ran for their young lives.

Jerry darted towards the container library. The container is mounted on a raised concrete platform. If he climbed onto the platform, the vehicle could not pose any danger to him, he thought. The edge of the platform had a one-block layer. When Jerry got to the platform, he could not jump over it at once.

He tossed his right leg over the little wall and was about to raise his left leg across to safety.

Staff Sergeant Inusah Habib showing the exact spot Jerry was hit

It was too late.

The Toyota Corolla was haphazard when it broke loose from its lane. But it picked its target with unmistakable precision. It went directly to the platform, the exact spot Jerry was about to scale and slammed Jerry’s leg against the wall. The vehicle came to a violent halt, but the engine was still roaring. The driver of the vehicle had mistaken the accelerator for a brake, according to the police report, and kept her foot on it.

After the initial panic, those who had escaped, including Kwabena Bukari, rushed back to the scene. Jerry was still tapped between the vehicle and the raised platform. A man, who was driving past the school but stopped because of the situation, jumped onto the concrete platform of the library and lifted Jerry up.

His left leg was missing. And his right leg was fractured.

Jerry was too traumatised to cry. When he was lifted up, he looked down and realised his left leg was gone. Mr. Bukari remembers a facial expression that looked like a smile. But all attention was on Jerry, and not the missing leg. He was quickly rushed into another vehicle and taken to the hospital.

Jerry at the 37 Military Hospital before his surgery in January 2017

“It was when we pushed the car backwards that we saw the other leg under the bonnet,” says Mr. Bukari. “There were also broken bones on the ground so we gathered everything into a polythene bag and took it to the hospital.”

Doctors at the Effia Nkwanta Hospital said the bones and the severed leg were useless.

At the Effia Nkwanta Hospital, the Coordinator of Schools at 2 Garrison in Takoradi, Staff Sergeant Inusah Habib, and a teacher in the school donated blood for Jerry, who was bleeding profusely.

Jerry’s father, Ebenezer Arthur, was numb with shock, when he got into the ward to see his son.

“When we got to the casualty ward, I saw the child. He said to me, “Daddy, I’m in pain. Daddy, I’m in pain.” When I looked towards his legs, I realised one of his legs was missing,” Ebenezer Arthur says.

He went on, “I could not react or show emotions because I was advised not to do anything to alarm him. I told him everything would be all right. They put a drip on him but as it continued, one of the soldiers was not impressed with treatment. He conferred with the headmistress and then called his superior and suggested a referral.”

Lt. Col. Livinstone Penti, the Officer in Charge of Education at 2 Garrison, made further calls to his superiors and arrangements were underway within 30 minutes for an evacuation of the boy. The army’s medical team arrived with an ambulance and Jerry was on his way to the 37 Military Hospital in Accra. Both of Jerry’s parents could not gather enough strength to go with their son so his uncle went with in the ambulance to Accra.

Jerry’s parents say but for the intervention of the military, they might have lost their son.

Jerry’s parents waiting outside their house in Takoradi for a taxi to take him to school, August 2018.

Wailing and prayers characterized the household that night. There was no appetite for food. His mother could not eat until the following day when she requested to go and see the exact spot her son was knocked down. She was compelled to eat “something small”.

“I thought seeing the spot of the accident would provide some relief, but it rather worsened how I felt,” Jerry’s mother says.

Betty Mensah and her husband have four children, two of them being hers. After their marriage, it took four years before she had the first seed of her womb, a girl. She had to wait another three years before Jerry was born. She wished for more, but the time and resources required to take care of Jerry (after his accident) made it imprudent to have another child.

At the 37 Military Hospital, the medical team diagnosed four issues with his condition:

- Crush injury right foot

- Open fracture right leg (Tibia/Fibula)

- Traumatic Amputation left leg

- Blunt abdominal trauma

Jerry in the hospital

Jerry’s mother got to the 37 Military Hospital three days later. She had longed to see her son, but when she finally did, she could not look at him. Her vision was blurred with tears. Jerry just stared at her blankly. He would not respond to his name, except tears from the pains he suffered. His mother was advised to leave the hospital because the crying did not only affect her but also the boy.

When she got to a relative’s house in Awoshie, a suburb of Accra, she had a call from the hospital.

“Jerry wants to see you,” her sister, who had joined her brother to take care of Jerry, told her over the phone. She did not leave the hospital until Jerry was discharged nearly seven months later.

Jerry spent about a year out of school. For several reasons, he could not return to the Garrison Basic School where the accident happened. The 2 Garrison Education Unit, led by Lt. Col. Penti, decided to take him to the Naval Base Basic School. That school was closer to Jerry’s home. Madam Elizabeth Cofie, who headed Garrison Basic School at the time of Jerry’s accident, had now been transferred to Naval Base Basic School.

Jerry is being taken to the Wednesday morning worship at the school’s assembly hall. Almost every facility of the school is not accessible by his wheelchair

“We thought she understood the boy’s condition better and would be in a better position to manage him,” Lt. Col. Penti explains.

The main reason Jerry has been transferred to another school was because his old school was not disability-friendly. A wheelchair cannot move to any of the classrooms. The toilet is far from the classroom and a wheelchair cannot get there.

Jerry has two wheelchairs, one at home and another in school. The one in school aids his movement and serves as his chair in the classroom. His new school, Naval Base Basic School, better accommodates his condition, but it cannot be said to be disability friendly either. His wheelchair can move to only one classroom unimpeded. To make this possible, the school had to construct a special rump at the entrance of this classroom.

Lt. Col. Livingstone Penti (right) welcomes Jeremiah Arthur after he was discharged from the hospital after the January 2017 surgery. The Ghana Airforce plane was flying to Takoradi and took them on board. Photo Credit: Public Relations Directorate of the Ghana Armed Forces

Jerry is in Primary 3, but it is the JHS block, which is accessible by wheelchair. For this reason, the school has moved Primary 3 to the JHS block and Jerry would spend the next six years in the same classroom until he leaves the school.

Jerry’s mobility is not the only burden the family has to deal with. The accident has left the family with serious financial challenges. The 37 Military Hospital absorbed part of his medical bills, but there’s still a lot of cost involved in the continuous medical treatments

“Now, we have to use a taxi anywhere we go,” Jerry’s mother explains. “Every morning he has to school in a taxi and come home in a taxi.”

“I had two Urvan buses and a taxi. I’ve sold one Urvan and the taxi. The remaining Urvan has broken down and is parked behind this workshop,” says Jerry’s father, Ebenezer Arthur, a car sprayer in Takoradi.

Jerry at a morning assembly in school

Jerry’s lawyers have begun legal processes to get him compensated, but it appears that might take a long time.

The driver of the vehicle, which knocked Jerry was a 62 year old spare parts dealer, Martha Amponsah. (She’s now 64.) She was charged with “dangerous driving” and “negligently causing harm”. She pleaded guilty to both charges and was sentenced to a fine of GHS1800 ($400), which she paid to the court.

Sources close to the scene of the accident allege she did not have the requisite documentations to drive the car at the time of the accident. A police report sighted by Joy News reveals the vehicle she was driving was registered in 2016, the year of the accident. Her driver’s license was issued on June 1st, 2016, just a day before the accident. The vehicle’s insurance was issued on June 2nd, 2016, the same day she knocked Jeremiah Arthur.

When Joy News contacted Martha Amponsah, she declined to comment on the accident. According to Jerry’s parents, she visits at an interval of three to six months and sometimes presents an envelope of between GHc200 and GHc300 to Jerry.

But Jerry’s family continue to bear

“The financial challenges are unbearable. When I speak to the woman, she talks about the insurance. The insurance company is yet to respond so I rely on loans. The pressure from the bank is what made me sell my vehicles.” Jerry’s father lamented.

Jerry’s mother has stopped selling food. Taking care of Jerry is her full time job.

Jerry with is siblings at home in Takoradi

“Imagine such a young child sitting in a wheelchair the whole day. Sometimes he tells me, ‘Mama Betty, I’m tired.’ When he wants to visit the toilet, I have to always be there to assist. I am now his leg. I cannot do anything,” she says.

Jerry is an intelligent boy with a promising future. This is a unanimous observation by his teachers and people who encounter him.

Jerry was in Primary One when the accident happened. When he returned to school, his colleagues were in Primary Three. He was taken to Primary Two, but the teachers soon realised he was brilliant enough to join his peers in Primary Three. They promptly promoted him, and he’s among the best three in the class.

Jerry wanted to be a soldier, a reason he was sent to a school run by the military. With a half leg, that dream appears over. He now shuffles between being a gospel artiste and a pastor of the Assemblies of God Church, where he worships.

Jerry in the classroom

Even though he is intelligent and has a promising future, that cannot wish away tall and thorny hurdles he must scale to reach his goal. As he grows, his movement in the school is going to be a challenge. His wheelchair can only access his classroom without a hindrance, and as he gets older and heavier, he cannot be carried around the compound by his teachers and his peers.

A health worker told Joy News it might be difficult to have a prosthetic leg because the amputation was very deep. Coupled with the fact that most facilities such as schools do not make provision for his condition, the future looks uncertain.

When I asked Jerry what he would desire if he had only one wish to make, he had no difficulty saying what it was.

“That wish must be to have another leg,” he said.

JoyNews’ Manasseh Azure Awuni spent months visiting Jerry and his family and often met them when they visited the 37 Military Hospital for medical reviews or surgery. The facts and narrations contained in this story are based on interviews with multiple sources of persons who witnessed the accident as well as reliance on medical records and police reports.

Those who feel touched to support Jerry can call his mother on 0540919129

-

Random Thoughts10 months ago

Random Thoughts10 months agoA Dutch Passport or a Ghanaian PhD?

-

Foreign News10 years ago

Foreign News10 years agoEvery Animal Meat Is Not Beef! See All Their Names

-

Manasseh's Folder12 months ago

Manasseh's Folder12 months agoManasseh’s Praise and Criticism of Akufo-Addo’s Action on the SML Scandal

-

Guest Writers9 years ago

Guest Writers9 years agoProf. Kwaku Asare writes: Nana Akufo-Addo has no law degree but…

-

Manasseh's Blog Posts9 months ago

Manasseh's Blog Posts9 months agoWho Started Free SHS?

-

Manasseh's Folder9 months ago

Manasseh's Folder9 months agoIs Napo Arrogant? And Does It Matter?

-

Anti-Corruption9 years ago

Anti-Corruption9 years agoMANASSEH’S FOLDER: Unmasking Afenyo Markins, NPP’s apostle of integrity

-

Manasseh's Folder9 years ago

Manasseh's Folder9 years agoEXCLUSIVE PHOTOS: Manasseh Azure Awuni marries “Serwaa”