Foreign News

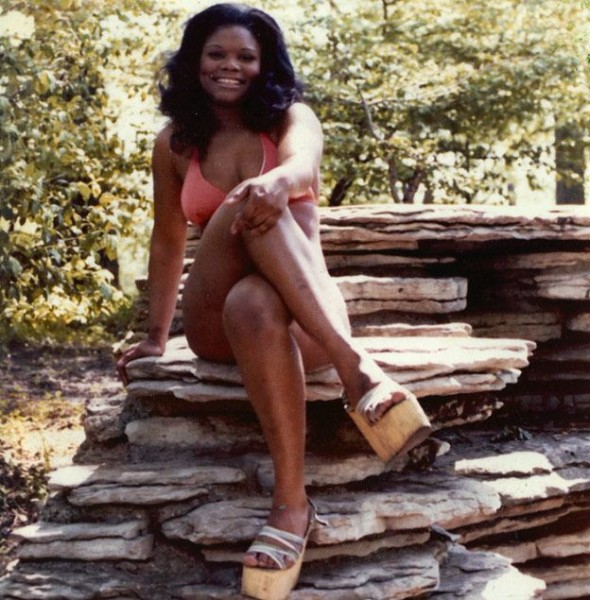

My 25 years as a prostitute

Brenda Myers-Powell was just a child when she became a prostitute in the early 1970s. Here she describes how she was pulled into working on the streets and why, three decades later, she devoted her life to making sure other girls don’t fall into the same trap. Some people will find Brenda’s account upsetting.

Right from the start life was handing me lemons, but I’ve always tried to make the best lemonade I can.

I grew up in the 1960s on the West Side of Chicago. My mother died when I was six months old. She was only 16 and I never learned what it was that she died from – my grandmother, who drank more than most, couldn’t tell me later on. The official explanation is that it was “natural causes”.

I don’t believe that. Who dies at 16 from natural causes? I like to think that God was just ready for her. I heard stories that she was beautiful and had a great sense of humour. I know that’s true because I have one also.

It was my grandmother that took care of me. And she wasn’t a bad person – in fact she had a side to her that was so wonderful. She read to me, baked me stuff and cooked the best sweet potatoes. She just had this drinking problem. She would bring drinking partners home from the bar and after she got intoxicated and passed out these men would do things to me. It started when I was four or five years old and it became a regular occurrence. I’m certain my grandmother didn’t know anything about it.

She worked as a domestic in the suburbs. It took her two hours to get to work and two hours to get home. So I was a latch-key kid – I wore a key around my neck and I would take myself to kindergarten and let myself back in at the end of the day. And the molesters knew about that, and they took advantage of it.

I would watch women with big glamorous hair and sparkly dresses standing on the street outside our house. I had no idea what they were up to; I just thought they were shiny. As a little girl, all I ever wanted was to be shiny.

One day I asked my grandmother what the women were doing and she said, “Those women take their panties off and men give them money.” And I remember saying to myself, “I’ll probably do that” because men had already been taking my panties off.

To look back now, I dealt with it all amazingly well. Alone in that house, I had imaginary friends to keep me company that I would sing and dance around with – an imaginary Elvis Presley, an imaginary Diana Ross and the Supremes. I think that helped me deal with things. I was a really outgoing girl – I used to laugh a lot.

At the same time, I was afraid, always afraid. I didn’t know if what was happening was my fault or not. I thought perhaps something was wrong with me. Even though I was a smart kid, I disconnected from school. Going into the 1970s, I became the kind of girl who didn’t know how to say “no” – if the little boys in the community told me that they liked me or treated me nice, they could basically have their way with me.

By the time I was 14, I’d had two children with boys in the community, two baby girls. My grandmother started to say that I needed to bring in some money to pay for these kids, because there was no food in the house, we had nothing.

So, one evening – it was actually Good Friday – I went along to the corner of Division Street and Clark Street and stood in front of the Mark Twain hotel. I was wearing a two-piece dress costing $3.99, cheap plastic shoes, and some orange lipstick which I thought might make me look older.

I was 14 years old and I cried through everything. But I did it. I didn’t like it, but the five men who dated me that night showed me what to do. They knew I was young and it was almost as if they were excited by it.

I made $400 but I didn’t get a cab home that night. I went home by train and I gave most of that money to my grandmother, who didn’t ask me where it came from.

The following weekend I returned to Division and Clark, and it seemed like my grandmother was happy when I brought the money home.

But the third time I went down there, a couple of guys pistol-whipped me and put me in the trunk of their car. They had approached me before because I was, as they called it, “unrepresented” on the street. All I knew was the light in the trunk of the car and then the faces of these two guys with their pistol. First they took me to a cornfield out in the middle of nowhere and raped me. Then they took me to a hotel room and locked me in the closet.

That’s the kind of thing pimps will do to break a girl’s spirits. They kept me in there for a long time. I was begging them to let me out because I was hungry, but they would only allow me out of the closet if I agreed to work for them.

They pimped me for a while, six months or so. I wasn’t able to go home. I tried to get away but they caught me, and when they caught me they hurt me so bad. Later on, I was trafficked by other men. The physical abuse was horrible, but the real abuse was the mental abuse – the things they would say that would just stick and which you could never get from under.

Pimps are very good at torture, they’re very good at manipulation. Some of them will do things like wake you in the middle of the night with a gun to your head. Others will pretend that they value you, and you feel like, “I’m Cinderella, and here comes my Prince Charming”. They seem so sweet and so charming and they tell you: “You just have to do this one thing for me and then you’ll get to the good part.” And you think, “My life has already been so hard, what’s a little bit more?” But you never ever do get to the good part.

When people describe prostitution as being something that is glamorous, elegant, like in the story of Pretty Woman, well that doesn’t come close to it. A prostitute might sleep with five strangers a day. Across a year, that’s more than 1,800 men she’s having sexual intercourse or oral sex with. These are not relationships, no-one’s bringing me any flowers here, trust me on that. They’re using my body like a toilet.

And the johns – the clients – are violent. I’ve been shot five times, stabbed 13 times. I don’t know why those men attacked me, all I know is that society made it comfortable for them to do so. They brought their anger or mental illness or whatever it was and they decided to wreak havoc on a prostitute, knowing I couldn’t go to the police and if I did I wouldn’t be taken seriously.

I actually count myself very lucky. I knew some beautiful girls who were murdered out there on the streets.

I prostituted for 14 or 15 years before I did any drugs. But after a while, after you’ve turned as many tricks as you can, after you’ve been strangled, after someone’s put a knife to your throat or someone’s put a pillow over your head, you need something to put a bit of courage in your system.

I was a prostitute for 25 years, and in all that time I never once saw a way out. But on 1 April 1997, when I was nearly 40 years old, a customer threw me out of his car. My dress got caught in the door and he dragged me six blocks along the ground, tearing all the skin off my face and the side of my body.

I went to the County Hospital in Chicago and they immediately took me to the emergency room. Because of the condition I was in, they called in a police officer, who looked me over and said: “Oh I know her. She’s just a hooker. She probably beat some guy and took his money and got what she deserved.” And I could hear the nurse laughing along with him. They pushed me out into the waiting room as if I wasn’t worth anything, as if I didn’t deserve the services of the emergency room after all.

And it was at that moment, while I was waiting for the next shift to start and for someone to attend to my injuries, that I began to think about everything that had happened in my life. Up until that point I had always had some idea of what to do, where to go, how to pick myself up again. Suddenly it was like I had run out of bright ideas. I remember looking up and saying to God, “These people don’t care about me. Could you please help me?”

God worked real fast. A doctor came and took care of me and she asked me to go and see social services in the hospital. What I knew about social services was they were anything but social. But they gave me a bus pass to go to a place called Genesis House, which was run by an awesome Englishwoman named Edwina Gateley, who became a great hero and mentor for me. She helped me turn my life around.

It was a safe house, and I had everything that I needed there. I didn’t have to worry about paying for clothes, food, getting a job. They told me to take my time and stay as long as I needed – and I stayed almost two years. My face healed, my soul healed. I got Brenda back.

Through Edwina Gateley, I learned the value of that deep connection that can occur between women, the circle of trust and love and support that a group of women can give one another.

Usually, when a woman gets out of prostitution, she doesn’t want to talk about it. What man will accept her as a wife? What person will hire her in their employment? And to begin with, after I left Genesis House, that was me too. I just wanted to get a job, pay my taxes and be like everybody else.

But I started to do some volunteering with sex workers and to help a university researcher with her fieldwork. After a while I realised that nobody was helping these young ladies. Nobody was going back and saying, “That’s who I was, that’s where I was. This is who I am now. You can change too, you can heal too.”

So in 2008, together with Stephanie Daniels-Wilson, we founded the Dreamcatcher Foundation. A dreamcatcher is a Native American object that you hang near a child’s cot. It is supposed to chase away children’s nightmares. That’s what we want to do – we want to chase away those bad dreams, those bad things that happen to young girls and women.

The recent documentary film Dreamcatcher, directed by Kim Longinotto, showed the work that we do. We meet up with women who are still working on the street and we tell them, “There is a way out, we’re ready to help you when you’re ready to be helped.” We try to get through that brainwashing that says, “You’re born to do this, there’s nothing else for you.”

I also run after-school clubs with young girls who are exactly like I was in the 1970s. I can tell as soon as I meet a girl if she is in danger, but there is no fixed pattern. You might have one girl who’s quiet and introverted and doesn’t make eye contact. Then there might be another who’s loud and obnoxious and always getting in trouble. They’re both suffering abuse at home but they’re dealing with it in different ways – the only thing they have in common is that they are not going to talk about it. But in time they understand that I have been through what they’re going through, and then they talk to me about it.

So far, we have 13 girls who have graduated from high school and are now in city colleges or have gotten full scholarships to go to other colleges. They came to us 11, 12, 13 years old, totally damaged. And now they’re reaching for the stars.

Besides my outreach work, I attend conferences and contribute to academic work on prostitution. I’ve had people say to me, “Brenda, come and meet Professor so-and-so from such-and-such university. He’s an expert on prostitution.” And I look at him and I want to say: “Really? Where did you get your credentials? What do you really know about prostitution? The expert is standing in front of you.”

I know I belong in that room but sometimes I have to let them know I belong there. And I think it’s ridiculous that there are organisations that campaign against human trafficking, that do not employ a single person who has been trafficked.

People say different things about prostitution. Some people think that it would actually help sex workers more if it were decriminalised. I think it’s true to say that every woman has her own story. It may be OK for this girl, who is paying her way through law school, but not for this girl, who was molested as a child, who never knew she had another choice, who was just trying to get money to eat.

But let me ask you a question. How many people would you encourage to quit their jobs to become prostitutes? Would you say to any of your close friends or female relatives, “Hey, have you thought of this? I think this would be a really great move for you!”

And let me say this too. However the situation starts off for a girl, that’s not how the situation will end up. It might look OK now, the girl in law school might say she only has high-end clients that come to her through an agency, that she doesn’t work on the streets but arranges to meet people in hotel rooms, but the first time that someone hurts her, that’s when she really sees her situation for what it is. You always get that crazy guy slipping through and he has three or four guys behind him, and they force their way into your room and gang rape you, and take your phone and all your money. And suddenly you have no means to make a living and you’re beaten up too. That is the reality of prostitution.

Three years ago, I became the first woman in the state of Illinois to have her convictions for prostitution wiped from her record. It was after a new law was brought in, following lobbying from the Chicago Alliance Against Sexual Exploitation, a group that seeks to shift the criminal burden away from the victims of sexual trafficking. Women who have been tortured, manipulated and brainwashed should be treated as survivors, not criminals.

There are good women in this world and also bad women. There are bad men and also good men.

Following my time as a prostitute, I simply wasn’t ready for another relationship. But after three years of healing and abstinence, I met an extraordinary man. I was very picky – he likes to joke that I asked him more questions than the parole board. He didn’t judge me for any of the things that had happened before we met. When he looked at me he didn’t even see those things – he says all he saw was a girl with a pretty smile that he wanted to be a part of his life. I sure wanted to be a part of his too. He supports me in everything I do, and we celebrated 10 years of marriage last year.

My daughters, who were raised by my aunt in the suburbs, grew up to be awesome young ladies. One is a doctor and one works in criminal justice. Now my husband and I have adopted my little nephew – and here I am, 58 years old, a football mum.

So I am here to tell you – there is life after so much damage, there is life after so much trauma. There is life after people have told you that you are nothing, that you are worthless and that you will never amount to anything. There is life – and I’m not just talking about a little bit of life. There is a lot of life.

Credit: BBC

-

Random Thoughts8 months ago

Random Thoughts8 months agoA Dutch Passport or a Ghanaian PhD?

-

Foreign News10 years ago

Foreign News10 years agoEvery Animal Meat Is Not Beef! See All Their Names

-

Manasseh's Folder9 months ago

Manasseh's Folder9 months agoManasseh’s Praise and Criticism of Akufo-Addo’s Action on the SML Scandal

-

Manasseh's Folder7 months ago

Manasseh's Folder7 months agoIs Napo Arrogant? And Does It Matter?

-

Guest Writers8 years ago

Guest Writers8 years agoProf. Kwaku Asare writes: Nana Akufo-Addo has no law degree but…

-

Manasseh's Blog Posts7 months ago

Manasseh's Blog Posts7 months agoWho Started Free SHS?

-

Manasseh's Folder8 years ago

Manasseh's Folder8 years agoEXCLUSIVE PHOTOS: Manasseh Azure Awuni marries “Serwaa”

-

Guest Writers6 years ago

Guest Writers6 years agoIs “Engagement” a Legal Marriage?